Donner à voir

15. Januar – 14. März 2015

Médiathèque Fonds d’art contemporain, Genève

Donner à voir war eine temporäre Konstellation von Filmen und Videos von Chantal Akerman, Michel Auder, Simone Bitton/Catherine Poitevin, Jean-Paul Fargier, Véronique Goël und Abderrahmane Sissako sowie einer Photo-Installation von Jan Lemitz.

Die Auswahl wurde kuratiert von Tobias Hering auf Einladung von und in Zusammenarbeit mit Raphaël Cuomo und Maria Iorio. Zum Programm gehörte auch eine Vorführung des Films Un autre été (1981) von Véronique Goël. Donner à voir war Teil von Unfinished Histories, einem dreijährigen Programmzyklus, den Raphaël Cuomo und Maria Iorio auf Einladung des Fonds d’art contemporain de la Ville de Genève in deren Mediathek organisiert und ko-kuratiert haben.

Programmtext [nur auf Englisch]

„Organiser toute l’exposition autour de cette tache aveugle…“ (Jacques Derrida in Mémoires d’aveugle by Jean-Paul Fargier) – to organise an entire exhibition around a blind spot. The blind spot of Donner à voir is the very gesture which puts itself at the beginning: giving something to see, a gesture at work both in filming and curating, an offer, an opening, a making-possible-to-see, but also the manoeuvre by which the visible is about to obliterate the invisible.

The videos selected from the collection of the Médiathèque Fonds d’art contemporain de la Ville de Genève (FMAC), as well as from its expanded content encountered in the physical holdings (cabinets, shelves, drawers, etc.) on site in Geneva, are all, in very different ways, narrative; they explore narrating as a practice that originates in a sense of absence and they furnish what is given-to-see as an evocation of that which is no longer or not yet visible.

1

Mémoires d’aveugle de Jacques Derrida

Jean-Paul Fargier, 1991, 52′

In 1990 the philosopher Jacques Derrida was given carte blanche for an exhibition from the vast collection of drawings at the Musée du Louvre. Derrida, who had never before curated an exhibition, chose to focus on the theme of „blindness“. The exhibition title, Mémoires d’aveugle („memoirs of a blind man/woman“, but also „memoirs of blindness“, or even „blind memory/memoirs“), refers not only to the common theme of the drawings he selected, but was also meant to describe Derrida’s own predicament as an inexperienced curator with the freedom to choose from a blinding wealth of material. Jean-Paul Fargier’s video stars Derrida himself reciting parts of a text he wrote on the occasion of the exhibition and its topic. Taking his cues from Derrida and the artworks referred to, Fargier lets the video image perform as a slippery surface for the simultaneous inscription and translation of the philosopher’s lucid meditation on blindness. Video = I see? Fargier’s attempt to visualize a discourse which is largely about the invisible produces astonishingly literal moments, some comical and subtle, some earnest and slightly gawkish.

2

Sud (South)

Chantal Akerman, 1999, 71′

In Sud, Chantal Akerman revisits the sites of the hate murder of James Byrd, Jr. in the rural town of Jasper, Texas. But that is something which only gradually manifests itself. For contemporary audiences (Akerman made the film only a few months after the incredibly brutal crime of June 1998), quiet travelling shots of a southern US town and its surroundings filmed from a smoothly moving car might have been conspicuous, or possibly unbearable. Over 15 years later, however, we find ourselves guessing what makes these utterly common aspects qualify for such painstaking observation. Gradually then, with the aid of interspersed statements by residents of the community, we come to understand what we are actually looking at. The invisible comes to the fore, until in the end it inhabits every square inch of the landscape.

3

Rostov-Luanda

Abderrahmane Sissako, 1997, 59′

A photograph taken in Rostov-on-Don in 1980 serves Abderrahmane Sissako as a jittering compass on a journey to Angola in 1995. The photograph is a group shot of seven foreign students with their Russian language teacher. Sissako himself is in the picture, and standing behind him, an Angolan student, Afonso Baribanga. Sissako remembers him as a young revolutionary from a country whose recent liberation from Portuguese colonialism had epitomized the aspirations of their generation. Sissako’s journey to Angola is dedicated to finding Afonso Baribanga. In 1995, Angola had just recently emerged from three decades of war, and Sissako’s search for someone he had last seen in Russia in 1982 with the help of only a single photograph seems utterly anachronistic and futile. It turns out, however, that the unfittedness of Sissako’s project suits the tattered state of the country. The blind spot at the core of his quest, the tenacious absence of Afonso Baribanga, fuels a free-wheeling road movie full of surprises.

4

So Long No See

Véronique Goël, 2009, 16′

So Long No See is an epitaph to a recently deceased friend, sound technician Luc Yersin, who had once sparked in Véronique Goël „a connivance with sound and my obsession with it“ and with whom she collaborated on several of her films, before their lives‘ trajectories seem to have wandered „out-of-sync“. Allusions to film sound, to the modes of producing it, its narrative qualities and to the dislocating effect of losing it, all reverberate in the narrator’s letter to a mutual friend, film-maker Stephen Dwoskin, read off-screen. So Long No See was made from the rushes of what would have become a sort of sequel to Soliloque 2/la Barbarie, Goël’s third collaboration with Yersin, created during a four-day shoot in Berlin in 1982. The sequel, however, conceived as a series of travelling shots from Berlin’s overground trains in 2008, never emerged as a finished film; instead the beginnings and ends of each take were recycled to describe the particular form of absence created by a particular death.

5

Backstage

Véronique Goël, 1999, 8′

When the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Geneva Convention was celebrated in the Forces motrices building in Geneva, Véronique Goël happened to be present with a small video camera. Sitting at the back of a large hall in which the soon to be opened buffet is being prepared, her framing is fixed on the enormous video screen at the other end of the room transmitting the commemorative speech given by Cornelio Sommaruga, then president of the International Committee of the Red Cross, in the adjacent auditorium. By revealing a disturbing simultaneity of activities, the unusual perspective provides a chance mise-en-scène which deconstructs the benevolent discourse trickling from the screen in the very moment of utterance.

6

Chronicles/Morocco

Michel Auder, 1972, 26′

Morocco 1972: the Real Chronicles with Viva

Michel Auder, 1972/2002, 36′

Chronicles/Morocco and Morocco 1972: the Real Chronicles with Viva are two very different video diaries of the same trip, edited 30 years apart. In the context of Michel Auder’s earlier experiments with film and video, the family vacation to Morocco was probably expected to yield a sequel to artist couple Auder and Viva’s notorious Family Diaries, which chronicled their life in the force field of Warhol’s „Factory“ and had previously included Viva being pregnant and giving birth to their daughter Alexandra. In the 1972 edit from the Moroccan footage, however, Viva and Alexandra remain largely absent from the frame. Rather than a family diary, Chronicles/Morocco initially appears to be an introverted, somewhat unfocused record, before a young Moroccan man takes all the attention, whose exhibitionist impromptu turns into an objet trouvé in the video’s collection of „savage beauties“ ‒ a term coined by Viva in the voice-over of the second version. In this 2002 re-edit of the footage, Auder omits the „Moroccan Adonis“ and composes instead the chronicle of a strenuous family trip complete with diarrhoea, condescending remarks on „the Arabs“, and washing diapers in the roaring ocean.

Auder later accounted for Viva’s virtual absence from the first edit by relating it to the tension that had grown between them en route and that had ultimately caused Viva to leave him a few weeks into the trip. With this information, The Real Chronicles, featuring Viva prominently in the image and behind the camera, often filming and narrating simultaneously, readily appears as a settling of scores. What remains unaddressed by this settlement, however, is a detachment which both edits suffer from: the hyperbolic representation of „the other“ whose expressions are made to appear cryptic and enigmatic ‒ an effect not only of the language and cultural gap, but also of what might be called Auder and Viva’s self-othering. Loss of focus, imbalanced framing, obstructed perspectives, truncated off-screen conversation become video evidence of what Viva at some point comes to describe as „mirage business“.

7

Conversation Nord-Sud: Serge Daney et Elias Sanbar

Simone Bitton, Catherine Poitevin, 1992, 48′

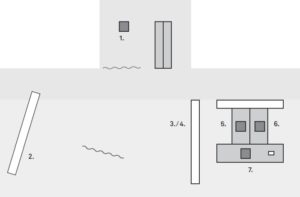

Sichtungstisch/Viewing table. Photographs and disappearing components.

Jan Lemitz, Photographs, glue, tape, table top, wood

Voici une image, „here is an image“, says Palestinian historian Elias Sanbar to French film critic Serge Daney, „an image of death“. The encounter between Sanbar and Daney was staged for television on the 4th of July 1991 in a bistrot on the Place de la Bastille in Paris. Their conversation is guided by a mutual showing of photographs which both had apparently been told to bring to their meeting; it weaves the personal with the political, the ephemeral with the iconographic. Sanbar’s „image of death“ shows a group of men in uniforms from which someone, a friend, is missing. The reason he is missing is simply that it was he who took the photograph; yet less than a year later, Sanbar remembers, this same friend had actually died. The photograph made him think that death is an „empty space in a landscape“, and he says that since then he has not been able to look at groups of people on images without seeing first and foremost the empty spaces between them, the places of those who are absent.

Furthering the resonance of this peculiar speaking from/of photographs, photographer Jan Lemitz was invited to create a spatial response around the video’s presentation in the exhibition. Lemitz’s intervention, Sichtungstisch/Viewing table, draws on his own collection of photographs as well as recent findings in archives to address the peculiar absences he sees inherent in every photograph. Letting associations and notions of familiarity bridge discontinuities and annexe the pictures on the table in spite of all inconsistencies – as happens between Sanbar and Daney -, the arrangement speaks of the respective ‚biographies‘ of the selected photographs, while also reflecting on the spatial conditions of presenting them in dialogue. The starting point for Lemitz’s intervention is an aerial photograph of the North Sea coastline near Calais, an image retained from the artist’s ongoing research on migratory movements and the history of the Channel Tunnel, depicting a landscape that reveals as much as it conceals.

Contemporary Art Center, Auditorium, March 8, 18.00

Un autre été

Véronique Goël, 1981, 87′

In fixed shots of equal length, Un autre été tells of the daily lives of a group of young men who earn their living by posting advertisements through mail boxes. Shot on black-and-white 16mm film in Geneva and its surroundings, Un autre été captures the silent catastrophe of normality: the loss of acuteness and ferocity in life in exchange for a numbing routine that pays the bills. Yet, far from being a period film on disenchantment, Un autre été, by delineating the soundscape as an autonomous zone, finds ways to re-enchant absences, to sabotage indifference and make silences speak. If Luc Yersin, the sound technician to whom Goël dedicated her short film So Long No See (shown in the exhibition), initiated the artist’s „connivance and obsession with sound“, Un autre été is an invitation to enter this complicity, and to experience with a gaze that, to borrow an idea from Georges Didi-Huberman, looks back at us from that which we behold.

Many thanks to Raphaël Cuomo and Maria Iorio, Véronique Goël, Jan Lemitz, Laurence Bonvin as well as Stéphane Cecconi, Lionel Coudray, Michèle Freiburghaus and Thomas Maisonasse at the Fonds d’art contemporain de la Ville de Genève.