Remembering the public performance project Sinop komün’ikasyon, directed by Emre Koyuncuoğlu, at Sinopale #1 in Sinop (Turkey) in 2006

Sinop 2006, photo: Tobias Hering

I came to Istanbul in April 2006 with the idea to stay for some months. From earlier visits I knew a few people in the city. They gave me reasons to come, but there was no project, no plan really. I rented a flat on Nemlizade Sokak in Kadiköy from a Swiss artist who had lived in Istanbul for several years and felt that she needed a break. The flat had a roof terrace from where I could see Haydarpaşa. At that time there were still trains going in and out of the station and they made me think of the possibility to travel further from here.

Berlin

A month before going to Istanbul I had organized a screening of the film La Commune – Paris 1871 in public space in Berlin as part of a political film festival which I continued to be engaged in over the next five years. Coming to Istanbul I imagined to do something similar with the film here and wrote a kind of exposée without really knowing yet who to submit it to.

La Commune- Paris 1871 is a six hour long re-staging of the historic events of the Paris Commune in 1871. Working with non-professional actors in an abandoned factory hall and employing extensive detail research into the events and its protagonists, director Peter Watkins revives the revolutionary climate of the times, the suffering, the hopes, the despair, the fears and the ideals of the people who seized power for two months after a spontaneous uprising in the 11th arrondissement of Paris on March 18.

Watkins’ style is quite original and can be called “pseudo documentary”. He combines meticulous truthfulness to historic facts with a strong interest in drawing parallels and revealing the ongoing relevance of the historic events facts and their usefulness in understanding contemporary political and social clashes, conflicts and crises. La Commune is one of several of Watkins’ films which stage historic (or possible future) events in a straightforward and strikingly realistic manner. But unlike most other “pseudo-documentary” films of his, La Commune employs an obvious break in its “realism” by introducing an impossible TV camera into the 1871 events. Strangely though, this “artificial” measure helps to present the events in an even more complex and lively manner. By not letting the camera be an anonymous and invisible eye for which the events are being staged and performed, but rather having it participate in the events, the film invites such issues as the role of the media in revolutionary movements and the question whether there can be such a thing as a “neutral spectator”, especially when something collective like a revolution is about to take place.

About the recent screenings in Berlin, I wrote:

The film’s six hours were split into three nights of two hours each, which were again split into chapters of 30 to 45 minutes length. Thus it was possible to screen the film at different locations, involving a mostly residential, low-to-mediate-income area around Berlin’s “Ostbahnhof” train station [and the “Straße der Pariser Kommune”, the Paris Commune Street, which had survived the large-scale renaming of East Berlin streets after 1989]. The different locations were chosen according to their accessibility, “casualness” and visibility, encouraging an imaginative and self-confident use of public space. The event was intended to be a political intervention into public space with the film as the “message”. On two occasions a performer “intervened” before the screening, highlighting questions raised in the film and also relating to the particular location. The audience was given hand-outs which summarized the historic events and underlined the contemporary relevance of the political issues. The screening locations were about 10 minutes walking distance from each other, so that the event was by itself turning into a small demonstration. The technical equipment was on a push-cart that was drawn by hand, thus underlining how easy it is to occupy public space in his manner.

What I didn’t mention was that it had been snowing on us on all three nights in Berlin and that we had been accompanied by a police van; a mere formality which however made the event less casual than intended. Someone told me afterwards that he had loved it for its “precarity”; I guess I had imagined it with a bit more revolutionary grandeur.

Istanbul

In the exposée, I then tried to describe what I found hard to imagine yet – a public screening of La Commune at different locations in Istanbul. Besides being a newcomer to the city and having no idea how and where to obtain permission for such a use of public space, another big obstacle was the language:

Even though the film provides a lot of “action”, the content is mostly conveyed through dialogue and discussion. Where background information is needed to contextualize a particular scene, Watkins has added explanatory inter-texts. The original language is of course French. As far as I know, the film has never or rarely been shown in Turkey. There is no version with Turkish subtitles. Showing the film here in a foreign language would be highly counteracting the intention to make it available to a diverse audience. The language problem would be even more acute when showing the film in public space. It would be a downright affront, to the film and to the audience, since it would mean to exclude a large group of people which could have a particular interest in the issues the film tackles. The problem then is how to bridge the language “gap”. My idea is to narrate the film’s events and discussions in Turkish in frequent breaks (beforehand or in retrospect, i.e. before each “chapter” or afterwards). These summary narrations could be turned into a performance in their own right by letting them develop into word-by-word re-enactments of crucial scenes of the film.

This feature would not only help to communicate the film’s content to a Turkish speaking audience, but it would also add an additional level of “adaptation” to the event: part of the film’s peculiarity comes from the non-professional cast’s unique embodiment/adaptation of the historical protagonists and their very original way to mingle their characters with their real life experience. Re-enacting parts of the film in front of the screen would stretch this time-link further to the present, the Turkish language thus becoming not only the medium, but a part of the message: we are all concerned by these issues today. Rather than simply producing a Turkish translation in subtitles or voice-overs, a performance seems a more worthwhile and original way to deal with the “language gap”. After all, this gap stands for the distance that any performance or presentation of this sort has to bridge in order to reach a specific audience at a specific time and place.

Quoting myself here, I realize how I was driven by a naive optimism and trust in the tools I was proposing for this difficult operation – translation, summary, performance, re-enactment, adaptation – and in reaching an audience ready to agree that “we are all concerned by these issues today.” The problem of “translation” became the reason to think of the project as a performance. I discussed this with a close friend, curator Fatoş Üstek, and she recommended to contact Emre Koyuncuoğlu. Emre became the first person to read the exposée, and it was under her eyes that whatever potential it had turned into possibilities; my naivete was aided by her imagination, experience, concerns, and practical sense. Her reading was already in fact the first of many translations in this process: gleaning from the exposée what was useful and applicable to a Turkish context. In our first meeting we still discussed the project as something to be done in Istanbul, and Emre came up with the working title “Istanbul komün’ikasyon.” I learned a lot. For example that the Paris Commune had been a point of reference for the young Kemal Atatürk, but also about sites in the city that could be identified with recent and current occasions of unrest and resistance.

A problem was where to get some funding from. While I was getting ready to contact some German foundations who had branches in Istanbul, Emre received an invitation to participate in the first edition of an art biennial in Sinop on the Black Sea coast, and she suggested that we propose our project there. It didn’t mean big budget, but it gave us a frame to work in. Within days, the imagination of La Commune in public spaces in Istanbul was replaced by the proposal to do “something” with the film in a fortress that had been a prison for several centuries. “Istanbul komün’ikasyon” became “Sinop komün’ikasyon”. Renaming was the easy part; everything else became a huge challenge for everyone involved.

Now, fourteen years later, Emre has been asked to contribute to Sinopale 8 with a proposal to revisit “Sinop komün’ikasyon”. She sent me an email, we met on zoom. The first question that posed itself through this invitation was how to remember a performance. What do we remember, what had been archived and how can it be accessed? How do you revisit, remember, reconstruct, or reconsider something that took place at a specific moment at a given place, and that had been a personal and eminently physical experience for us, for the performers, and for those who finally came to take on the role of “the audience”? While this touches on fundamental questions of archival politics and history writing, it also reposes once again a core question of the project itself: How can a personal experience be transmitted, told, narrated, and be recognized as part of a shared history? How can we act within the always imminent danger that writing history can mean to erase the actual experience of lives? How do we begin to speak, when what is most important to transmit is often that which is hard to speak about or for which there are no words and no witnesses?

While copying material from our hard drives, re-reading notes, contacting the performers, we also recognized that new gaps had opened up since 2006 and that the past we have been asked to bring to the present feels much further away than it should.

Sinop

About a month before the opening of the biennial in 2006, I had gone to Sinop for a few days to see the town and the prison and to conceive of how our “piece” could communicate with the place. Emre had begun to gather a group of collaborators in Istanbul, dancers she had worked with before, people with a theater background, a journalist, a social worker, inviting all of them to not only bring to the project their particular skills, but also their knowledge, sensitivity and attitudes, as much as they were willing to. While I was in Sinop, a curious stranger in a town that luckily was used to curious strangers, Emre and the group were collecting ideas and elements for something that we conceived of as a combination of excerpts from the film, choreographed movements and texts spoken or read aloud.

The question is what to do with the prison. Bright large rooms which only darken when one imagines 60 prisoners cramped into them, sometimes for life. Wide open courtyards from which separation walls had been removed in order to make them more accessible for cultural events – to become “stages”, said the guide, but her English was so unreliable that I shouldn’t take what I understood for granted. If something was “not important”, for example, it only meant that it wasn’t written on her crib sheet. In one of the large group cells in the women’s wing she pointed at a row of hooks high up on the walls and said: “Hanging.” I understood that female prisoners were suspended on these hooks as a means of punishment. Yet the hooks looked more like coat hangers. I found out that in fact they were. But why that high? About 3,50 Meters above the ground? “Not important”. At some point I started filming the guide looking up answers in her notes and in the dictionary. On the cover of her notebook was written: “Lovely Times.” In it were written the most important facts about the prison, for example that one day two prisoners had tried to escape through the sewers. One of them got out, but he was captured again two weeks later. The other one drowned in the sewers. “So nobody ever escaped from this prison.” I doubt that this is true. The girl studies “Tourist Guide” in Safranbolu. I asked her if that was equivalent to studying local history. She disagreed: “History? Why?”

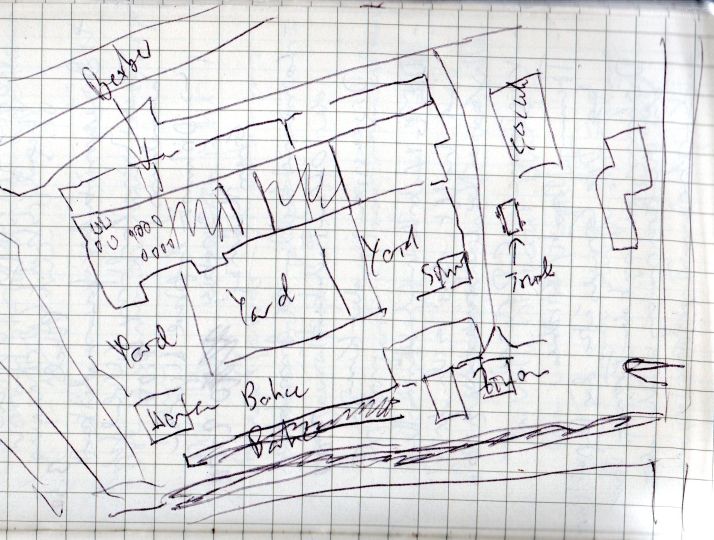

Notebook sketch of Sinop prison layout

On these first days, it wasn’t clear to me yet what to do with the film, where to screen it: inside the prison or somewhere in town. I walked from one end of the town to the other with an eye out for walls that could be turned into temporary screens.

I like the banality of the town and how it juxtaposes to the spectacular topography of the peninsular.

– a small basketball court with one basket and a small circular stand

– the shipyard: hammering, welding, grinding on bulky boats. A large unfinished boat, rusty all over. Orkan says it has been lying here since seven years. They had started to build it, then abandoned it. The clanging and buzzing sounds from within the bodies of mid-sized ships. I find it hard to tell whether they are being built or dismantled. Is this repair work or recycling?

– a long pier stretching out to the sea (which means that it stretches back towards the coast due to Sinop’s crooked shape)

– a platform by the water, probably once a jetty for ferries, for getting on and off board; descending steeply, white concrete like a stage in floodlight. Seen from the tower: a horizontal screen with one single iron ring in its centre.

– at the edge of town, on the road to Karakum: an unfinished building, now a ruin; across the street stands a dilapidated wooden house and a proper little show-off building for the Belediye. The ruin, 5 or 6 floors high, with large, empty, square-cut gaps for the windows and a rounded corner wall facing the street. In a similar ruin at the opposite end of town I have seen laundry hanging in the empty concrete rooms.

– an empty lot in front of the ruined church on the hill is not even used for parking. The people up here probably cannot afford cars. It would be instructive to hear their stories, how they make use of the town from up here, from what seems to be a privileged vantage point. The ruin is surrounded by private gardens with artichokes, corn, cabbage, and something that looks like bolted broccoli.

– Community spaces: the municipal beaches, slim, more or less tidy strips of fine sand. There you see the same people lying in the sun whom you see in the shops and cafés and on the sidewalks and at the barbers. The women, slightly elevated in second row, well garmented, watchful of their children or grand-children, calling out to them every once in a while. The men, either half-buried in the sand by the children, or standing in the water up to their calves, hands on their hips. A pleasant scene, lacking the usual holiday props – umbrellas, paravents, stretchers, rubber animals, ice-boxes and plastic shovels, whose main purpose is to mark territorial claims.

Sinop 2006, photo: Tobias Hering

There were several reasons why in the preparation we worked on separate tracks. For once, there wasn’t a lot of time and things needed to be done simultaneously. Another reason was that we thought it best that each of us focused on their part of the puzzle. Related to this was again the language gap: Had I participated in the preparatory sessions with the performers, we would have needed a translator or conduct everything in various forms of broken English. This was out of the question, and with hindsight I am aware that it was a crucial decision (maybe Emre´s more than mine) to not force this project to look like a “transcultural collaboration” more than it was. The gaps needed to be accepted. Closing them would have been a pretension. The gaps were where the “audience” could come in and define their space.

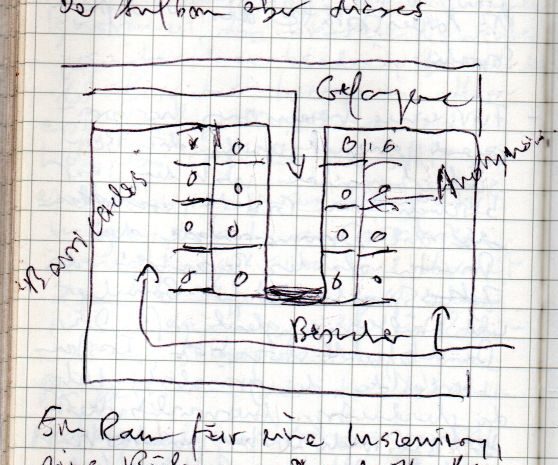

In the prison. The visitor booths with their nearly opaque separation grids are lending themselves to a choreography. Privacy as deprivation. The spaces for visitors and prisoners are equally sized. The terrible proximity while at the same time being out of reach. Above all, the irritating fact that one can walk around the bloc of booths to the “other side” but there only finds empty cells where one would have expected to meet the other – the disappearance of the other in the illusion to see both sides. The design is like this:

On the 2nd floor of the children’s prison there’s a room about 9 by 10 meters, the largest interior room in the entire wing with arched windows on three sides and an ocean view. The idea to screen the film onto the ceiling, the audience lying on their backs and the performers intervening from the windowsills, motioning to each other above their heads: a murmur, a rumor, a discourse. The audience given cover, but also passive, reduced, numbed; yet at the same time comfortable, relaxed, at ease.

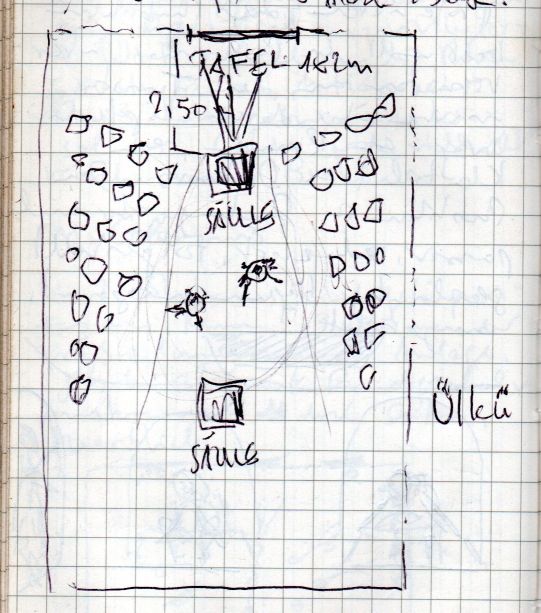

The classroom:

Sinif

Sinema

6 by 9 meters, windows at two sides.

Due to the pillars the audience will be seated in a triangular shape with two “wings”; projection to the blackboard.

ÇALISANA ALLAH İLMİ VERİR 1963

The performers act in the triangular space between the pillars.

In almost all the courtyards there was a small kitchen in one corner and a barber. These shacks now remind me of the devastated film set in the opening scenes of La Commune. There are more things here that make me think of a film set, and in fact the place was occasionally used as one in recent years. One can tell by the fresh paint on the walls in some places.

The narrow aisles with the regularly spaced doors. Representations of an order planned from above and suffered on the ground.

In one of these aisles, along the back of the cell buildings, doors to the left are leading to the courtyards, while on the right there are niches, about 3 meters wide and 1 meter in depth, carved into the 15 meters high stone wall. Small stages, small scenes.

The Selçuks, the Byzantines, the Romans, the Turks, the Ottomans – the buildings bear only faint traces of history. The majority of traces are those left by tourists, phrases, vows, declarations of love, names, and phone numbers on the walls. The site has only been open to the public since 1999, but this phase of its use has already almost erased the traces of the preceding ones. I wonder if the prisoners wrote on the walls as well, and if their words are now hidden among the scribble by the visitors, or if they have been painted over by the film crews.

Whatever will be done here during the Sinopale will be a perpetuation of these touristic uses; and it will only make sense, and be legitimate in the first place, if it picks up the threads which these kinds of use have abandoned or have not even touched. Whether one looks at the primitivism of this penal compound or at its efficiency, one always looks at a place where people have suffered, and others have done their jobs.

I am disinclined to conceive of performing something outside, in the open; in FREEDOM. But one must also work through (i.e. legitimize) the impulse to lock the audience in, to force them to the ground and to corner them. “To put them in the position of the other”.

Ironically, the most time-consuming task for my part of the puzzle was providing the Turkish subtitles for the segments from La Commune that we had selected for “Sinop komün’ikasyon”. I was lucky and am still grateful to have found three able translators for the task, Murat Musulluoğlu, Fatoş Üstek, and Rana Öztürk, who I am happy to see is also one of the co-curators of Sinopale 8. We have all come a long way since 2006, and to Fatoş Üstek I owe more thanks in this project than I could aptly express here. The translations were finished just when we were about to go to Sinop to rehearse for a week and then immediately present “Sinop komün’ikasyon” on three consecutive nights. While Emre and the group were rehearsing in the prison and adapting the choreography to the locations we had chosen, I spent hours on the balcony of the hotel room, editing the film excerpts and spotting the subtitles, a learning-by-doing process which my laptop was barely equipped for. For lunch we usually met in a restaurant downtown for which we had been given vouchers.

Through my previous connection with La Commune, I knew the people of “Le Rebond pour La Commune”, the Paris-based association of those who had participated in the film’s making and were now taking care of its distribution and dissemination. Part of their working with the film was to be present at screenings and to discuss the process of its making, sometimes reperforming elements of it in new contexts. When I told them about our plans in Sinop and asked them for permission to use excerpts from the film, they not only granted that, but also decided to attend the event as visitors. Patrick Watkins (son of director Peter Watkins and editor of the film), his partner Caroline Lensing-Hebben, who plays the role of a German bourgeoise in the film, and another member of the original cast, came to Turkey on their way to Georgia and made a stop-over detour to Sinop, arriving by night-bus from Istanbul in the morning of the premiere.

When Patrick announced they were coming, I described to him in an email where we were with “Sinop komün’ikasyon”:

We will work intensely on-location for a week starting Thursday and the final shape will be given to the piece there. Emre still produces ideas and links every day, continuously adding to the excitement. Last week she by chance attended a performance in a lawyers’ association building in Istanbul where lawyers, and I guess ex-convicts and journalists, re-enacted scenes from their daily dealings with the Turkish justice system. She filmed it and it looks to me somewhat “Watkins” style with a constant blending of character and person, a very engaged and furious performance, very raw. We want to use this video in some way as a little installation on its own. So you see that it is still work in progress, which is of course because we are dealing with issues of an extremely vital and political importance.

Again, practical reasons and constraints assigned my final role in the actual performance piece. The original idea to have projectors and loudspeakers installed at every location where a film excerpt was meant to be screened turned out unrealistic. There simply weren’t enough projectors, players and speakers available, so that the only way to present the film in parts was to carry the equipment along and to use the duration of the choreographed parts for setting up image and sound at the next screening location. That worked. It turned me into the “carrier” of the film, making me perform on each of the three nights what had actually been my initial contribution to the piece, and also bringing me full circle to the Berlin screenings in March, minus the snow.

Porto

Reading again how we thought about the project in 2006, Emre and I remember that we had expected “Sinop komün’ikasyon” to be the beginning of a series of similar site-specific projects with the film, the next one to take place in Istanbul. That never materialized. But we did get the chance to bring the concept to another location when we were invited by the gallery Ideas Emergentes from Porto to participate in a group show, titled “Red Line,” in 2008. The invitation came thanks to José Roseira, a writer, translator, social worker, bee-keeper, winemaker, and friend of mine, who felt that a collaborative project of this sort could become a platform for different groups living in Porto to come together and discuss the future of a city in which neo-liberal policies had led to estrangement and increasing social discrepancies. “Porto Comunidade” was again a workshop-based group project leading up to a performance piece, this time in public space, on Praça da Batalha, one of the busiest squares in the old town.

The Porto project began with screenings of parts of La Commune – Paris 1871 in several locations: an independent art space, a café, an anarchist project room. The idea was to start a collective process with a debate about the film and by making people interested in participating in a ten-day performance workshop beginning one week later. For the workshop, the gallery had managed to get access to a large hall in Fábrica Social, a former factory building that had become the work and exhibition space of well-known local sculptor, José Rodrigues, and the seat of the cultural foundation that bears his name. Within a few days, word of mouth and the introductory screenings had brought together a group of some fifteen people, most of them free lancers in the cultural scene of the city, willing to enter a collective experiment.

Like in Sinop, our idea with “Porto Comunidade” was to get people to express something which is not often said, although it concerns many if not everyone sharing a history and a space in time. Here the relation was not to a prison however but to public space. Praça da Batalha lies elevated at the skirt of what is today marketed as “the old town”. Historically, the site was where town and country were separated, where they met, and the name “square of the battle” seems to suggest that this encounter was not always smooth. Even today, when spending some time on the square one begins to see that it is still a site for encounters of very different walks of life.

Porto, Praça da Batalha, 2008 – photo: João Pádua

While in Sinop, Emre could relate to the location with a complex understanding of its significance, Porto was completely new to her. I had been in Porto frequently since 1998, had friends here and knew my way around the city. Still, I think I was a stranger to either site, Sinop and Porto, an observer, empathetic, and a bit overly eager to get involved. In both places I needed translation, and on both occasions I ended up in the performance, as a performer. In Sinop I carried the film around with me. In Porto the film was dispersed over the TV screens of the adjoining bars and cafés – the “Paula”, the “Chave Douro”, the “Tropical”, and the “Gazela”, which I was told was one of the few bars in town that were still run as a collective. This time I carried a boom-box, playing a CD with a 50-minute discourse of a woman about one of the few collective housing projects in the city – a Utopian island, as she called it. While walking around the square, a cigarette-pack-sized audio device was lodged in the breast pocket of my jacket, recording the sounds around me during the roughly two-and-a-half hours that we occupied the square.

Describing “Porto Comunidade” from memory is filtered by the fact that I had already done so once in 2010, when Colectivo Piso, a group of Porto artists who had moved to Berlin, asked me to contribute to a book dedicated to collective work processes. The book was titled State of Motion and came out in 500 copies in 2010. My contribution was the edited transcript of the audio recording I had made during the performance of “Porto Comunidade” on Praça da Batalha. I dedicated this text to António Oliveira, a blind accordion player and well-known character in Porto, who had recently died. Senhor António had not participated in the workshop, but he had accepted our invitation to play during the performance. After the only rehearsal we had with him a few days before, he had told me that things like this should be done “com mais tempo”, with more time.

I gave the transcript the title, “De nada”, which is the habitual response in Portuguese when someone says, “Thank You”. Literally, “de nada” means “for nothing”, and the ambiguity of that title shows how in 2010 my recollections of the Porto project were rather sober. For years after I remembered “Porto Comunidade” more for what I thought were its shortcomings than for what it might have achieved. The individual contributions which the workshop participants brought to the final performance were all strong, intuitive, mostly silent expressions of one person’s relation to the city and its public spaces. While they articulated interesting, often poetic dialogues with the space and those who use it, they didn’t seem to be in dialogue with each other. Again, there were gaps, fractures, awkwardnesses, this time possibly symptoms of a politics that had disencouraged the people of Porto to consider their city a collective project.

In Sinop, I felt, we had been more successful, although I couldn’t be sure, since I didn’t understand all that was said in the discussions with the audience after the performances. The invitation to revisit “Sinop komün’ikasyon” made me come to Istanbul and confront together with Emre these intense periods of collaboration at a time when we feel that coming together, creating bonds, building communities is more needed than ever. Our conversations, with hindsight, made me aware that while my personal memories are but a fraction of what there is to remember, dwelling on the marginality of one’s own perspective can also be a way to shun responsibility. I am very grateful for this opportunity to converse with earlier versions of myself, an exercise which, I think, also helps to foster tolerance for other people’s idiosyncrasies. Supporting respect for opacity and incoherence is one of the good uses of an archive, as long as we don’t fool ourselves by pretending that what has been archived is all there is to remember.

This text was written by invitation from Emre Koyuncuoğlu and in conversation with her, in Istanbul in May 2022. It was published as part of an online publication during Sinopale 8 in June 2022, but does not seem to be accessible any more in its published form.